RESOURCES

PEOPLE

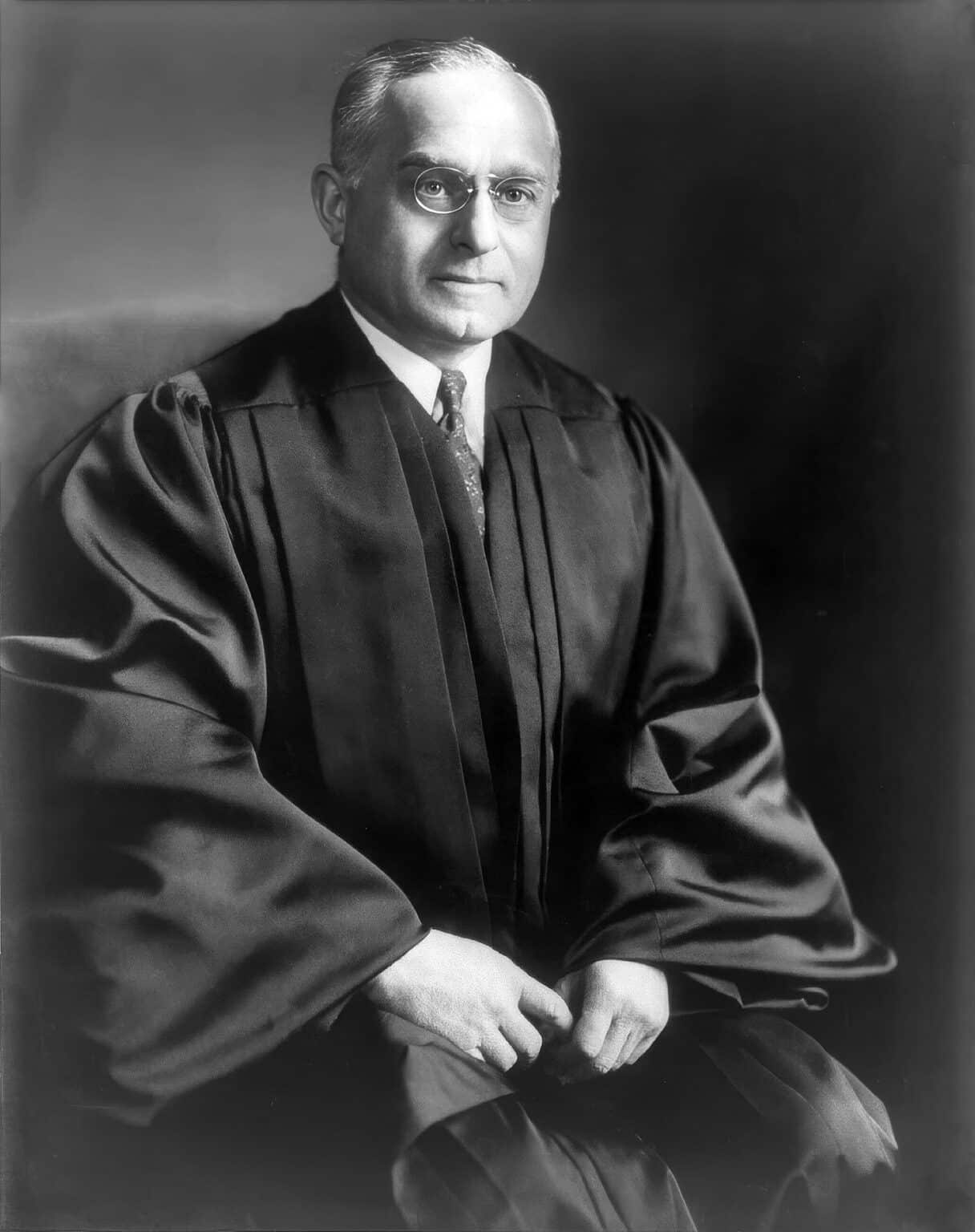

Justice Felix Frankfurter

1882-1965

Felix Frankfurter was born on November 15, 1882, in Vienna, Austria-Hungary, and immigrated to the United States with his family in 1894. Raised on the Lower East Side of New York City, he quickly distinguished himself academically. He graduated from City College of New York in 1902 and Harvard Law School in 1906, where he would later become a revered professor.

Frankfurter worked as an assistant U.S. attorney in New York and served as a legal advisor in the Wilson administration, notably helping to establish the War Labor Policies Board. A key figure in American legal thought, he co-founded the New Republic magazine and became a leading advocate of judicial restraint—the belief that courts should defer to the decisions of legislative and executive branches unless absolutely necessary.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Frankfurter to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1939. During his tenure (1939–1962), Frankfurter became known for his cautious, process-oriented approach to constitutional interpretation. He often opposed broad judicial interventions, even in cases where the outcome might have advanced progressive social goals.

Frankfurter’s role in school desegregation was shaped by his belief in judicial restraint and his strategic influence behind the scenes. He did not write the landmark 1954 opinion in Brown v. Board of Education, which declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional—Chief Justice Earl Warren did. However, Frankfurter played a pivotal role in shaping the Court’s approach.

Deeply concerned about public acceptance and the legitimacy of the Court’s ruling, Frankfurter strongly advocated for a unanimous decision to avoid regional backlash and maintain institutional credibility. He pushed for a deliberate and cautious pace in the deliberations, helping to delay the ruling while the justices sought consensus.

Frankfurter also influenced Brown II (1955), which addressed the implementation of desegregation. The Court’s vague directive that desegregation proceed “with all deliberate speed” reflected Frankfurter’s preference for gradualism and deference to local authorities. While this phrase was meant to prevent chaos, it was later criticized for enabling delay and resistance in the South.

Frankfurter, who retired in 1962 due to a stroke, witnessed this fallout and the challenges of enforcing Brown, a case in which he had invested considerable political and judicial capital. He died only three years after retiring, on February 22, 1965 at the age of 82.