GALLERY III

THE COURT SPEAKS

“We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

— Chief Justice Earl Warren in Brown v. Board of Education, May 17, 1954

The federal district court heard the Davis case February 23-25, 1952. County officials had hired the best lawyers in Richmond and were assisted by state Attorney General J. Lindsay Almond. They argued that segregation was fundamental to Virginia’s way of life. The district court ordered the county to end discrimination in education, but upheld the constitutionality of segregation.

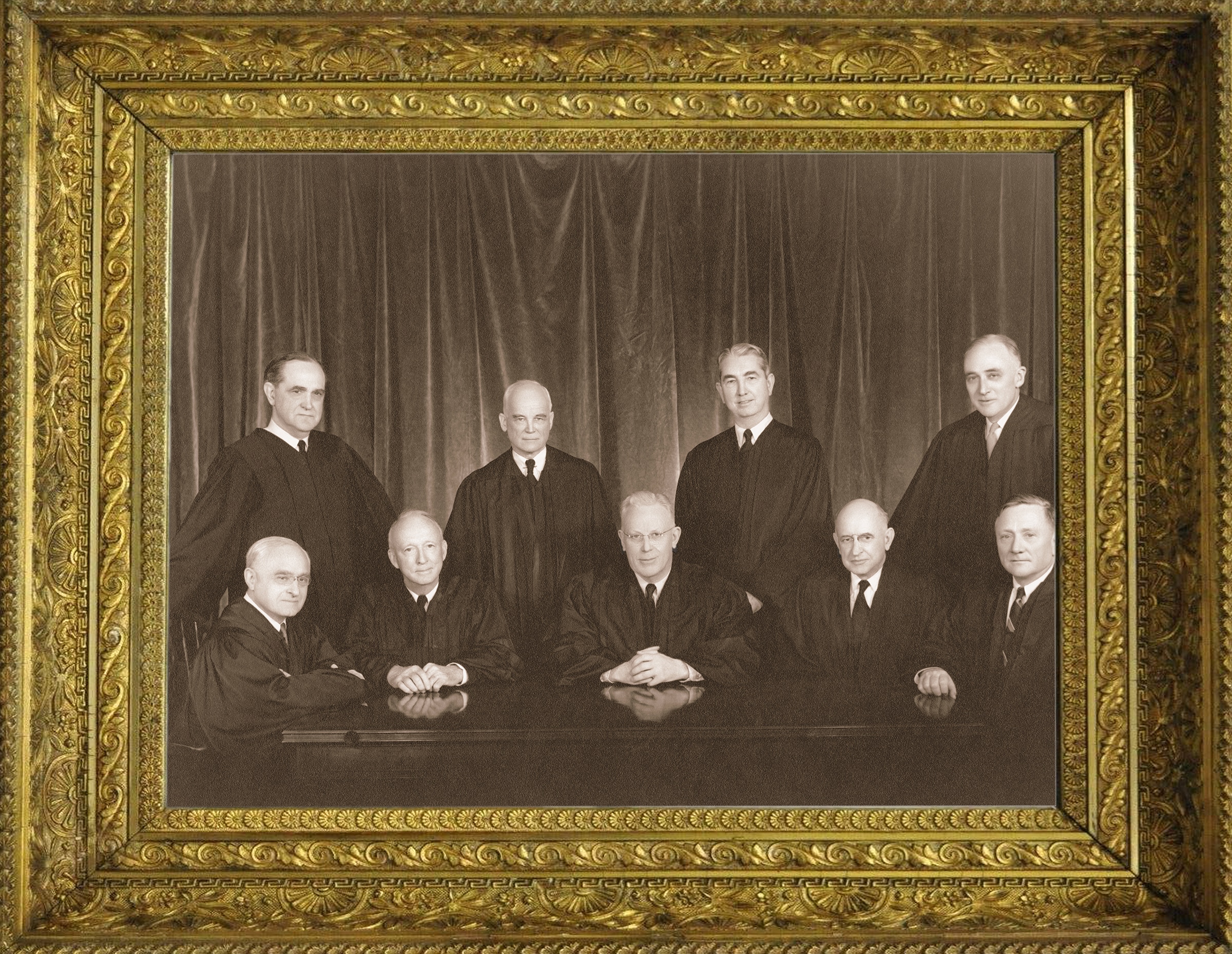

The Supreme Court heard arguments in the Brown cases in December 1952 and again in December 1953. On May 17, 1954, the Court declared segregation unconstitutional, but left unanswered the question of implementation. After further hearings, on May 31, 1955, the Court issued a second decision, often known as Brown II. The justices ordered the cases be remanded to the federal district courts, which were to “enter such orders…to admit to public schools on a racially nondiscriminatory basis with all deliberate speed the parties to these cases.”

FIGHTING FOR

DESEGREGATION

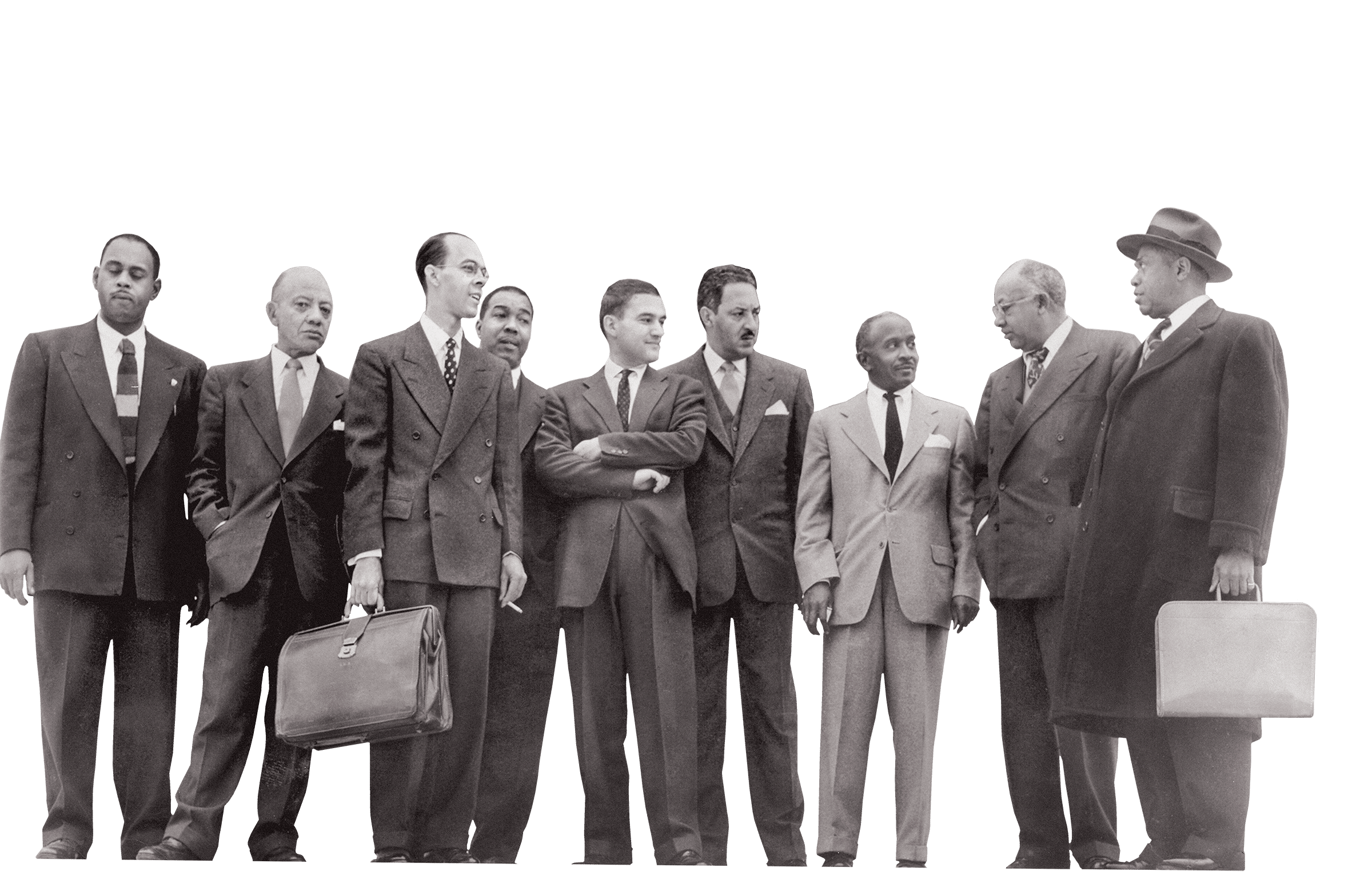

THE NAACP'S NATIONAL STRATEGY

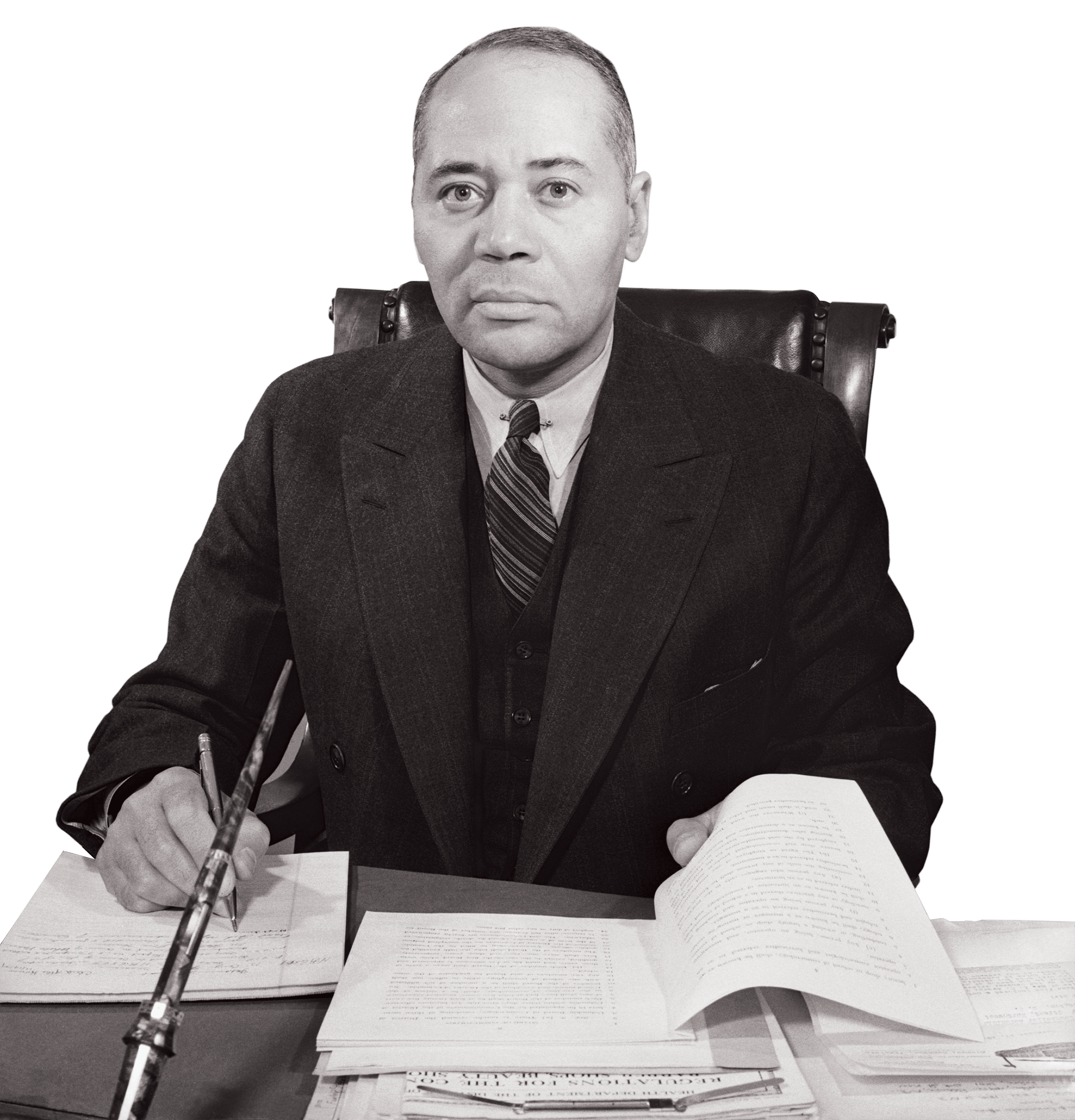

Charles Hamilton Houston

Thurgood Marshall

“The complete destruction of all enforced segregation is now in sight.... We are going to insist on non-segregation in American public education from top to bottom—from law school to kindergarten. ”

— THURGOOD MARSHALL, 1950

THE LAW FIRM OF HILL, MARTIN & ROBINSON

“Experience has proved...that the average white lawyer, especially in the South, cannot be relied upon to wage an uncompromising fight for equal rights for negroes.”

— THURGOOD MARSHALL

DEFENDING

SEGREGATION

“Certain persons posing as leaders of the Negro race have shocked many people in Virginia by advocating and urging the violation of the Constitution of our Commonwealth on the part of public school officials…

Segregation of the races in the public schools is called for in the fundamental law.

…It has been observed throughout the history of our Commonwealth and will continue to be observed…The white and Negro races have lived in harmony and mutual respect in Virginia longer than in any part of the Western Hemisphere."

— GOVERNOR WILLIAM TUCK, 1948

VIRGINIA'S DEFENSE

Attorney General James Lindsay Almond and Assistant Attorney General Henry T. Wickham represented the Commonwealth of Virginia.

“We were determined to show that segregation and discrimination were not the same thing."

— ARCHIBALD ROBERTSON

J. Lindsay Almond

BUILDING A CASE

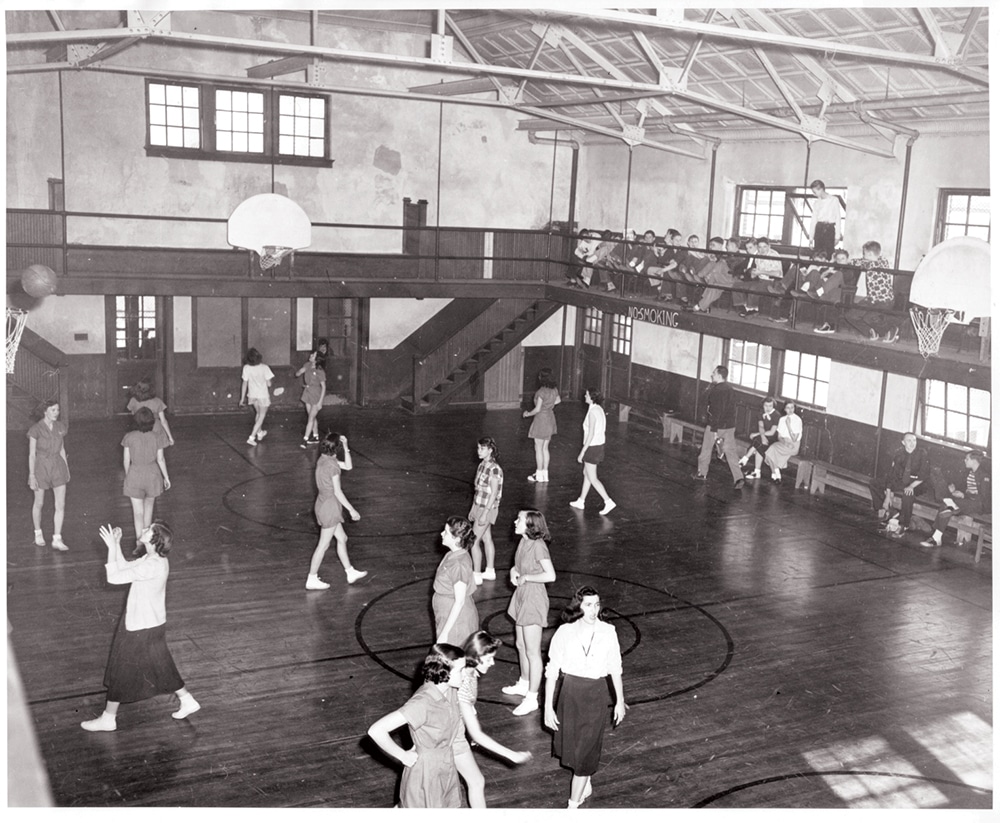

Farmville High School

“[We intend] to have the Prince Edward colored schools declared unequal and the Virginia segregation statute declared unconstitutional."

— SPOTTSWOOD ROBINSON III

“There is no foundation whatever for the fundamental theory on which this case is built—namely, that equal facilities and advantages cannot be provided regardless of the amount of money that is spent...."

— T. JUSTIN MOORE

CAN SEPARATE

BE EQUAL?

THE ROAD TO

BROWN

THE DAVIS RULING

“There was never any doubt about the outcome of the trial.... We were trying to build a record for the Supreme Court."

— OLIVER HILL

JUDGE STERLING HUTCHESON

BEFORE THE COURT:

THE CASE FOR SEGREGATION

The Brown Legal Team

A double line waited for the doors of the Supreme Court to open for another day of arguments on racial segregation in public schools.

“The Supreme Court will have to worry over community attitudes. Let us worry over the problem of pressing for our civil rights.... Let the Supreme Court take the blame if it dares say to the entire world, ‘Yes, democracy rests on a legalized caste system. Segregation of races is legal.’ Make the Court choose...”

— JAMES NABRIT, PLAINTIFF'S ATTORNEY, BOLLING V. SHARPE

A NEW CHIEF JUSTICE

September 8, 1953

March 1, 1954

“Any estimate of Warren’s career will mark him as one of the seminal figures not only of his own time, but of the years that followed his death.... Earl Warren was neither a student of government nor a judicial craftsman.... He had only an abiding sense of the public good—that, and a respect for personal values considered old-fashioned or even irrelevant to the business of governing."

— ED CRAY. CHIEF JUSTICE:

A BIOGRAPHY OF EARL

THE BROWN

CASES

FIVE COMMUNITIES

WAITING FOR A DECISION

Clarendon, SC

Washington, D.C.

Prince Edward Co., VA

Wilmington, DE

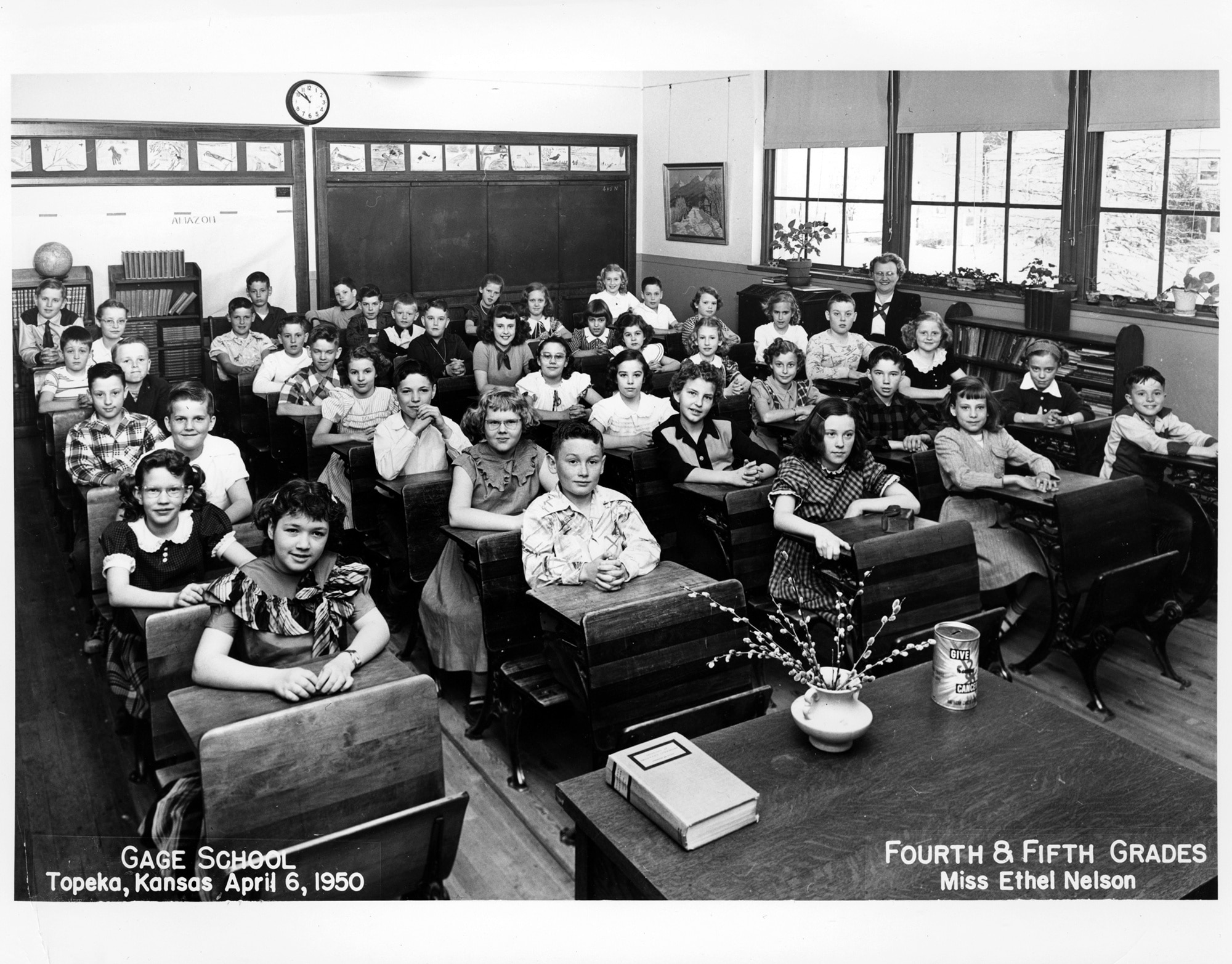

Topeka, KS

Clarendon, SC

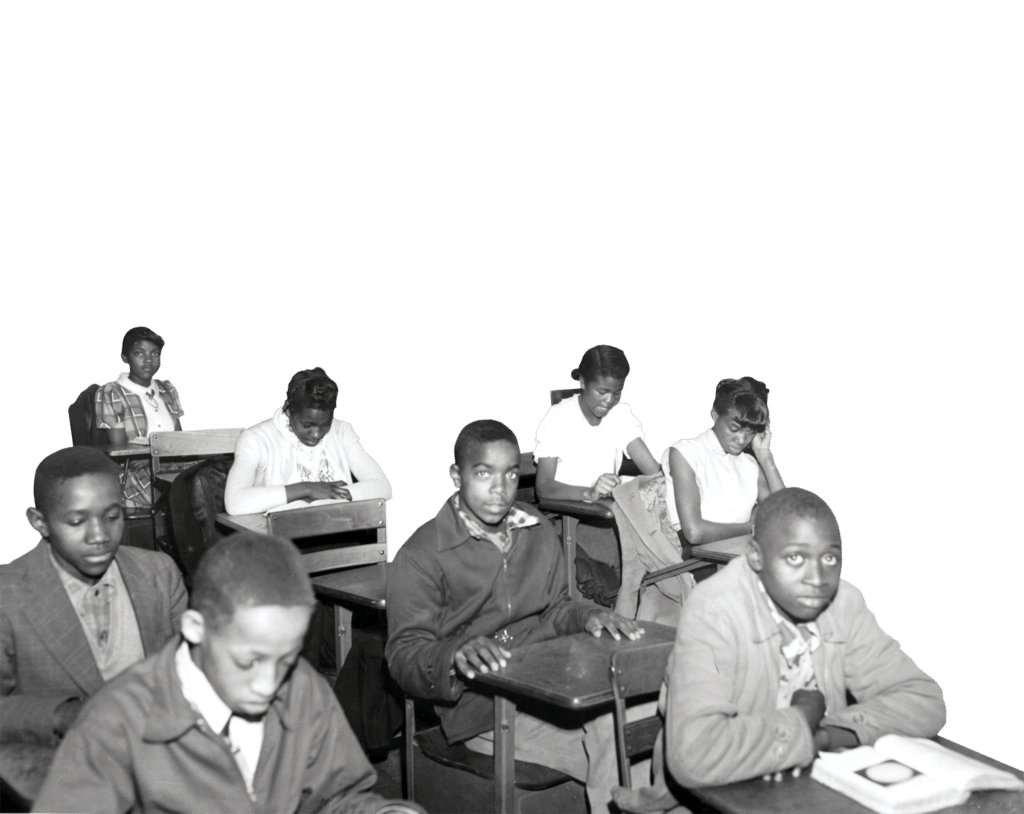

“The Negro child is made to go to an inferior school; he is branded in his own mind as inferior.... You can teach such a child the Constitution, anthropology and citizenship, but he knows it isn’t true."

— ATTORNEY THURGOOD MARSHALL, CONCLUDING REMARKS, BRIGGS V. ELLIOTT

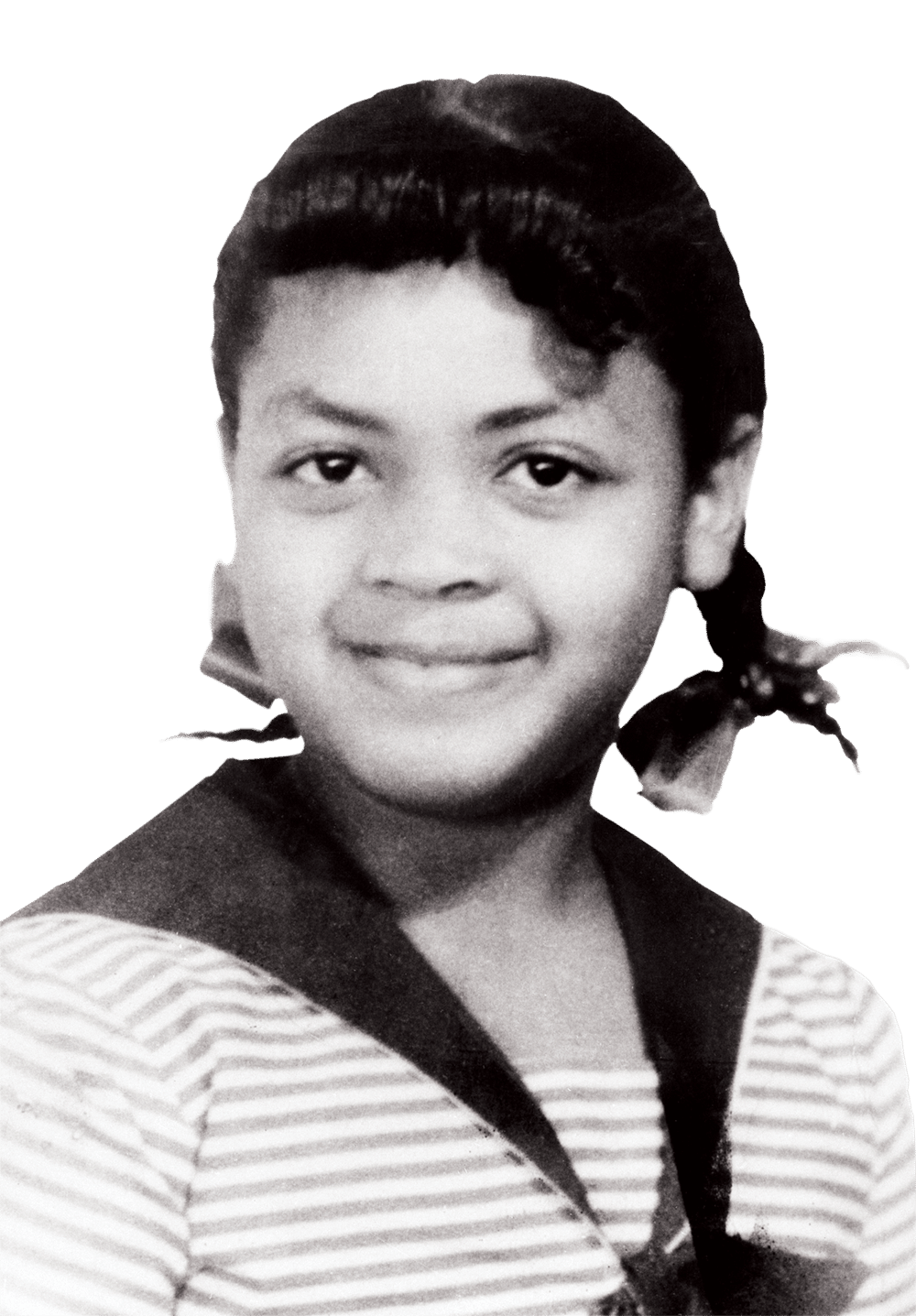

Eliza Briggs

Washington, D.C.

“You either have liberty or you do not. When liberty is interfered with by the state, it has to be justified, and you cannot justify it by saying that we only took a little liberty. You justify it by the reasonableness of the taking."

— ATTORNEY JAMES NABRIT, CONCLUDING REMARKS,

BOLLING V. SHARPE

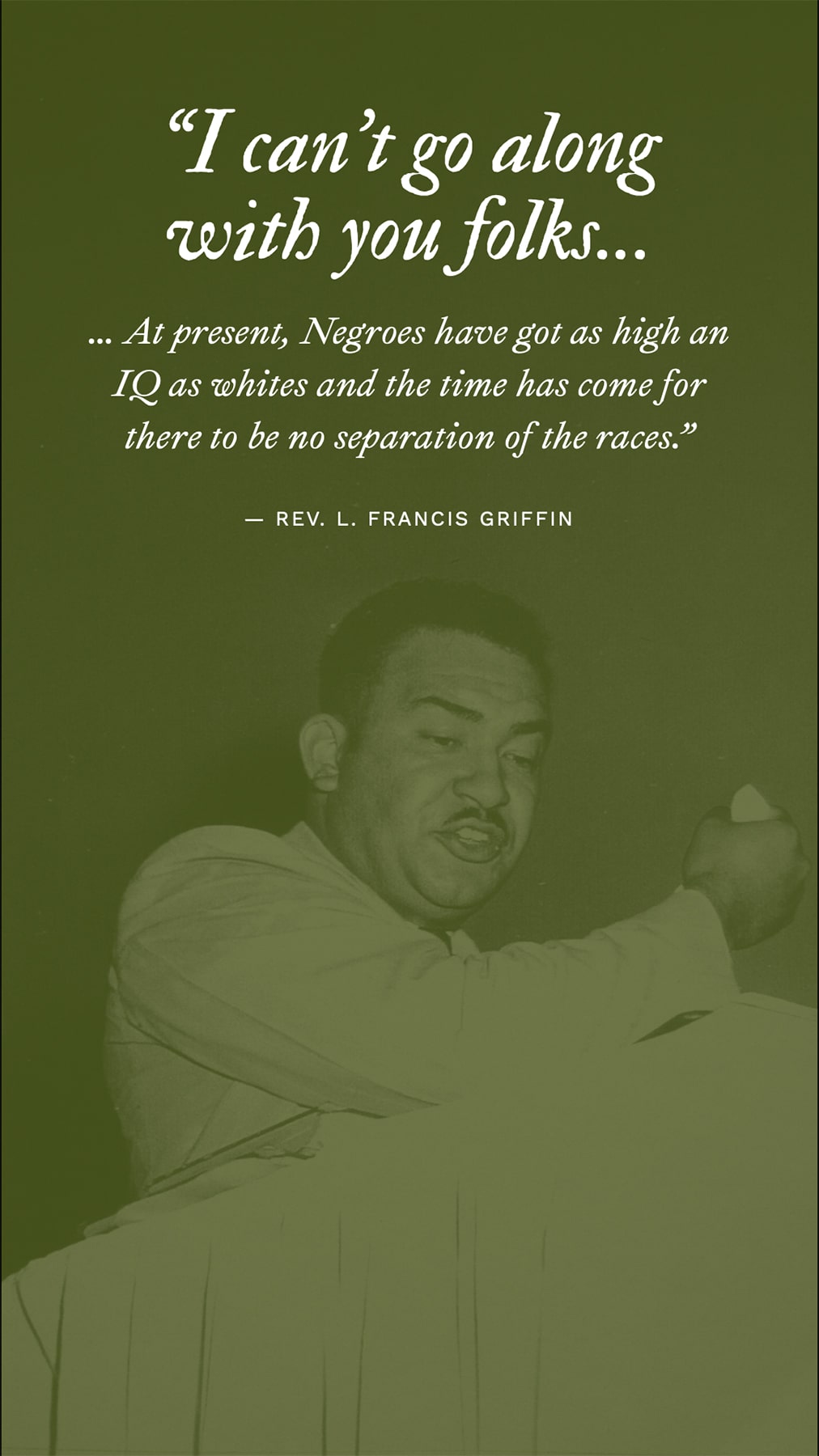

Prince Edward Co., VA

“Notwithstanding Virginia’s efforts in this case, it is clear that her racial policy in public education cannot be permitted to endure."

— NAACP SUPREME COURT APPEAL BRIEF, DAVIS V. PRINCE EDWARD

Wilmington, DE

“I believe the ‘separate but equal’ doctrine in education should be rejected, but I also believe its rejection must come from [the U.S. Supreme] Court."

— DELAWARE COURT OF CHANCERY JUDGE COLLINS SEITZ, OPINION IN BELTON V. GEBHART

MEANWHILE…

A NEW R.R. MOTON HIGH SCHOOL

“Is equity to be unmindful to the psychological truth that change, especially drastic change, takes time?"

— JUSTICE FELIX FRANKFURTER

THE DECISION: BROWN V. BOARD

May 17, 1954

“What the South was guilty of was an inherent determination that the people who were formerly in slavery, regardless of anything else, shall be kept as near that stage as is possible, and now is the time, we submit, that this Court should make it clear that this is not what our Constitution stands for."

— THURGOOD MARSHALL

“We come then to the question presented: Does segregation of children in public schools solely on the basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other ‘tangible’ factors may be equal, deprive the children of the minority group of equal educational opportunities? We believe that it does."

“We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place."

“Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. This disposition makes unnecessary any discussion whether such segregation also violates the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment."

— EXCERPT FROM THE 1954 BROWN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION U.S. SUPREME COURT DECISION

REACTION TO BROWN

“The highest court in the land has spoken, and I trust that Virginia will approach the question realistically and endeavor to work out some rational adjustment.”

— VIRGINIA ATTORNEY GENERAL J. LINDSAY ALMOND

BROWN II

“With all deliberate speed”

May 31, 1955

“While giving weight to...public and private considerations, the courts will require that the defendants make a prompt and reasonable start toward full compliance with our May 17, 1954, ruling."

— CHIEF JUSTICE EARL WARREN, DELIVERING THE OPINION OF THE COURT

“The practical difficulties which may be met in making progressive adjustment to a non-segregated system cannot be ignored or minimized....

A reasonable period of time will obviously be required to permit formulation of new provisions...in areas affected by the Court’s decision."— PHILIP ELMAN, SOLICITOR GENERAL’S ASSISTANT, FROM THE U.S. GOVERNMENT’S BRIEF, BROWN V. BOARD

“A program for ‘orderly and progressive transition’ to be carried out ‘within a specific period’ would serve to reduce any community antagonisms that might arise from a desegregation order."

— PHILIP ELMAN, SOLICITOR GENERAL’S ASSISTANT, FROM THE U.S. GOVERNMENT’S BRIEF, BROWN V. BOARD

“Because these cases arose under different local conditions and their disposition will involve a variety of local problems, we requested further argument on the question of relief."

— CHIEF JUSTICE EARL WARREN, DELIVERING THE OPINION OF THE COURT, BROWN V. BOARD II