RESOURCES

PEOPLE

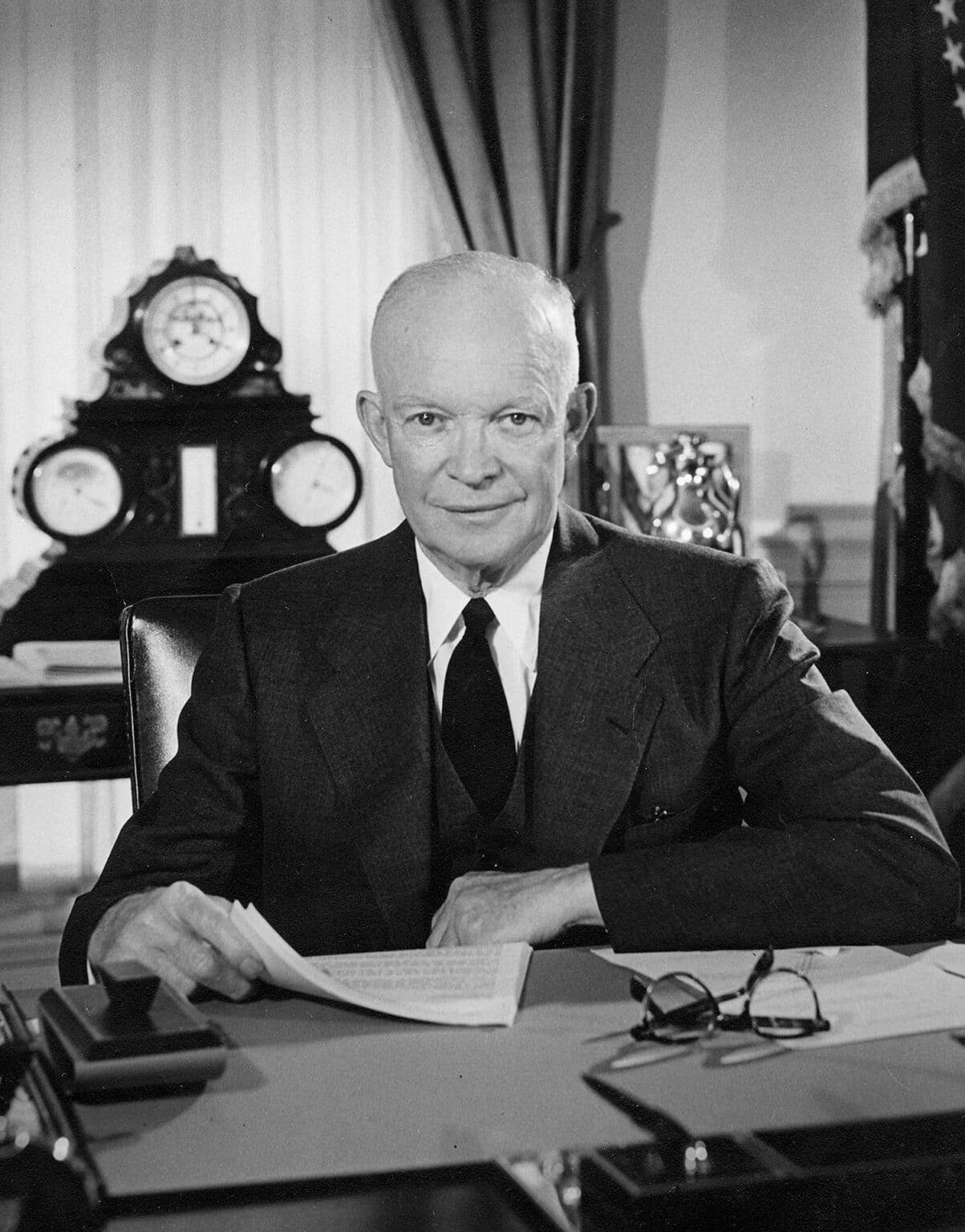

Dwight D. Eisenhower

1890-1969

Dwight D. Eisenhower, the 34th President of the United States, from 1953 – 1961, was a five-star general and the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe during World War II. His leadership of the D-Day invasion and his reputation for integrity, pragmatism, and calm judgment made him a popular figure across party lines. As president, Eisenhower sought to maintain stability during the Cold War while carefully navigating the early stages of the Civil Rights Movement—an area where his actions often reflected cautious pragmatism rather than moral urgency.

Eisenhower came from a modest background in Kansas and held personal beliefs that emphasized order, gradualism, and respect for institutional processes. These views shaped his approach to civil rights. Although not ideologically aligned with the emerging civil rights movement, Eisenhower understood the growing imperative for federal involvement in enforcing constitutional rights, especially in the South. His civil rights policy was incremental and legalistic, often aimed more at preserving federal authority than actively challenging racial injustice.

One of the most consequential decisions of his presidency was the 1953 appointment of Earl Warren as Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Warren, the Republican governor of California, had supported Eisenhower’s candidacy, and the appointment was initially seen as politically expedient. However, the Warren Court would quickly take a bold turn in advancing civil liberties—most notably with Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional. While Eisenhower enforced the ruling, he did so with visible reluctance and never publicly endorsed the decision in strong moral terms. He reportedly expressed personal discomfort with forced integration and often spoke more sympathetically about the Southern white resistance than the demands of African American citizens.

Despite his personal reservations, Eisenhower acted decisively in key moments. In 1957, he sent federal troops to Little Rock, Arkansas, to enforce court-ordered school desegregation when the state’s governor used the National Guard to block African American students from entering Central High School. This marked the first time since Reconstruction that a president had used federal troops to uphold civil rights, setting a critical precedent for the federal enforcement of Supreme Court decisions.

In legislative terms, Eisenhower signed the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first civil rights law since Reconstruction. Though its impact was limited by Southern opposition and weak enforcement mechanisms, it established the U.S. Civil Rights Commission and recognized the federal government’s responsibility to protect voting rights. He followed it with the Civil Rights Act of 1960, which aimed to strengthen enforcement, though again with modest effect.

Eisenhower’s civil rights legacy is one of restrained intervention—marked by legal and constitutional commitments rather than moral leadership. He avoided public alignment with civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., preferring behind-the-scenes efforts that preserved federal authority without sparking national upheaval. Yet his actions, especially the appointment of Earl Warren and the enforcement of school desegregation, had far-reaching consequences. They signaled the beginning of a federal role in civil rights enforcement and laid the groundwork for the more transformative legislation and activism that would follow in the 1960s.