RESOURCES

COURT CASES

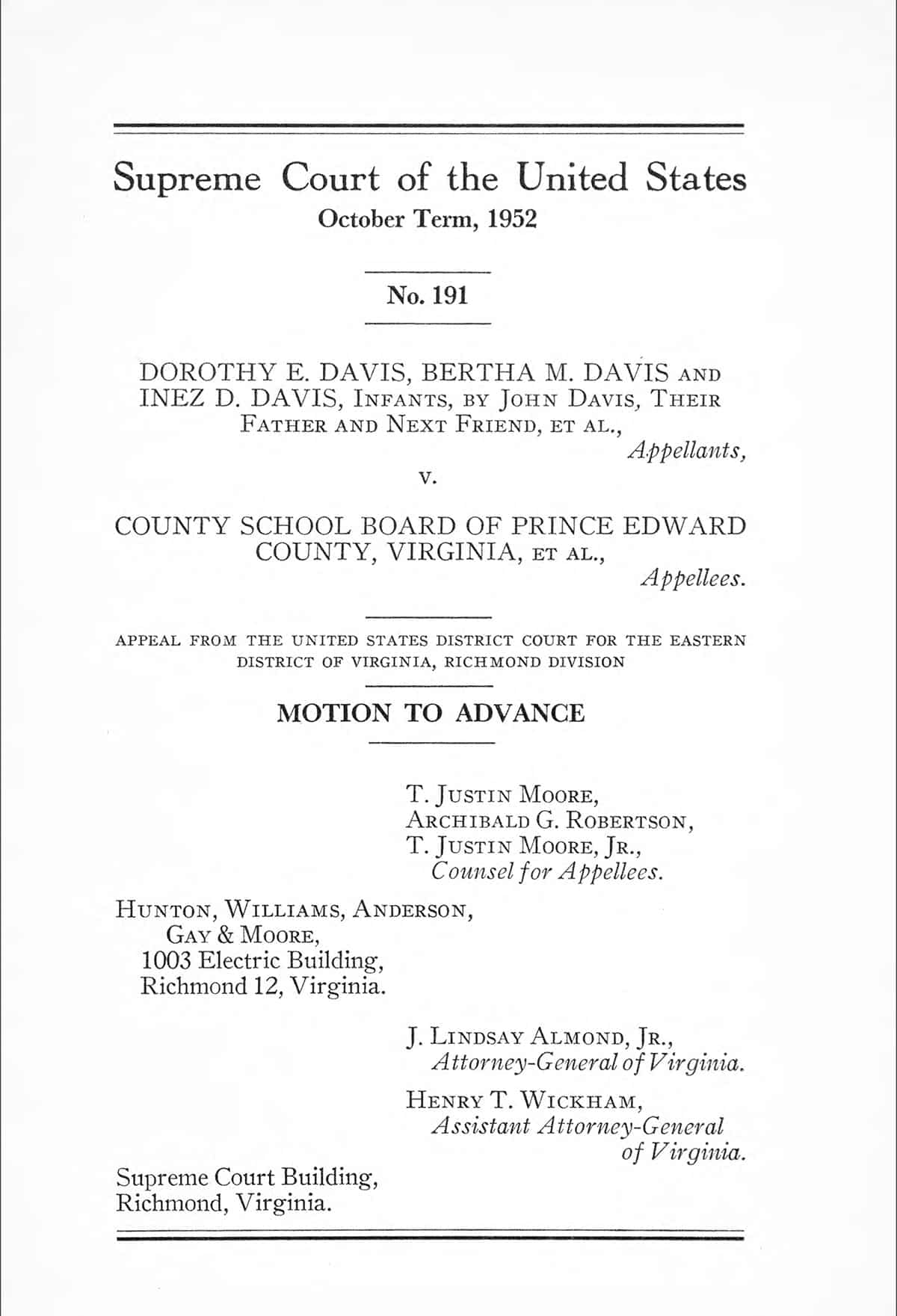

Davis v. Prince Edward County Board of Education

1951

In the early 1950s, the educational system in Prince Edward County, Virginia, was segregated under the “separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). In reality, the facilities for Black students were vastly inferior. Robert Russa Moton High School, built in 1939 for Black students, was overcrowded, underfunded, and lacked basic facilities like a gym, cafeteria, and adequate heating.

On April 23, 1951, 16-year-old Barbara Johns led a walkout of over 450 students, protesting these conditions. The students demanded a new school building, and the protest drew attention from the NAACP, which agreed to take up their case—but only if the students and their families were willing to challenge segregation itself, not just fight for better facilities.

The defense, representing the school board, argued that segregated schools could be equal in quality.

Filed in May 1951 in U.S. District Court in Richmond, Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County named 117 student plaintiffs. NAACP attorneys Oliver Hill and Spottswood Robinson argued for the plaintiffs that segregation violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. The defense, representing the school board, argued that segregated schools could be equal in quality.

Dorothy E. Davis was a 15-year-old student at Robert Russa Moton High School when she joined the 1951 student strike led by Barbara Johns. She was one of the 117 Black students who agreed to be part of the legal challenge filed by the NAACP, but her name appeared first on the list of plaintiffs — a common legal practice — making her the named plaintiff in the case.

In 1952, the federal court upheld segregation, citing Plessy v. Ferguson. However, it acknowledged the unequal facilities and ordered the county to begin building a new high school for Black students.

The NAACP appealed, and the case was consolidated into Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, heard by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1952–1953.

In 1954, the Supreme Court issued its Brown v. Board decision, unanimously ruling that segregated schools are inherently unequal and violate the 14th Amendment.

However, Prince Edward County became one of the most resistant localities in the South. In 1959, rather than integrate, county officials closed all public schools for five years, denying education to Black students while white students attended private “segregation academies” funded with public money. This led to the Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County case, in which the Supreme Court in 1964 ordered the schools to reopen and integrate.