RESOURCES

COURT CASES

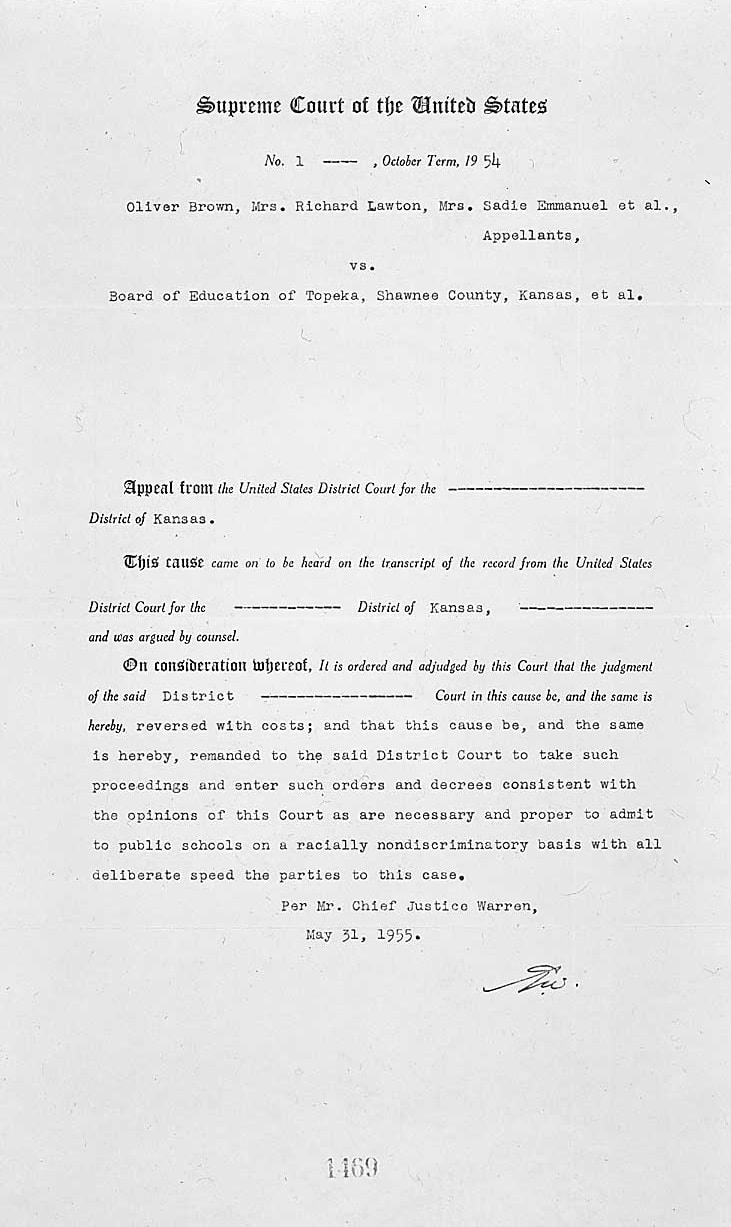

Brown v. Board of Education

1954

Brown v. Board of Education (1954) was a landmark Supreme Court case that fundamentally reshaped American public education and civil rights law. While it is often remembered as a single lawsuit, Brown was in fact a consolidation of five separate cases from different regions of the country, all coordinated by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund under the leadership of Thurgood Marshall. Each case challenged the constitutionality of racial segregation in public schools, and together they formed a unified legal front to attack the precedent established by Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which had allowed “separate but equal” facilities.

Brown v. Board of Education was a landmark Supreme Court case that fundamentally reshaped American public education and civil rights law.

The five cases were:

1.Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas – A case involving elementary school segregation in a northern, urban setting where Black students were denied admission to nearby white schools.

2.Briggs v. Elliott (South Carolina) – Originating in a rural district with stark disparities between Black and white schools in terms of resources, facilities, and transportation.

3.Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (Virginia) – Sparked by a 1951 student-led strike over poor conditions in a segregated Black high school.

4.Gebhart v. Belton (Delaware) – Unique because the state court ruled in favor of the Black plaintiffs, ordering integration before the federal Supreme Court acted.

5.Bolling v. Sharpe (Washington, D.C.) – Challenged segregation in federally operated schools under the 5th Amendment, since the 14th Amendment applies only to states.

These cases were consolidated by the Supreme Court not only for judicial efficiency, but to underscore the national scope of school segregation and to present a diverse array of conditions—rural and urban, North and South, state and federal. The legal strategy aimed to demonstrate that segregation was inherently unequal regardless of geography or relative school quality. Each case brought different facts to bear: some emphasized inadequate facilities, while others showed that even when facilities were materially similar, the very act of separation inflicted psychological harm on Black children.

The NAACP’s legal team, including Marshall, Spottswood Robinson, Robert Carter, and Jack Greenberg, crafted a constitutional argument grounded in the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, but they also incorporated social science evidence—most famously the “Doll Test” by psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark—to show how segregation fostered feelings of inferiority among Black children. They argued that separate schools stigmatized children and violated their right to equal educational opportunity, no matter how well the schools were funded or maintained.

The Supreme Court took the extraordinary step of holding two rounds of oral arguments, first in 1952 and again in 1953, and even requested additional briefing on whether the framers of the 14th Amendment had intended to bar school segregation. Ultimately, in a unanimous decision delivered on May 17, 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” thus overturning Plessy in the realm of public education. By combining these five cases, the Court addressed the issue with broad national authority and ensured that the ruling would be seen as a mandate for desegregation in every part of the United States.