RESOURCES

COURT CASES

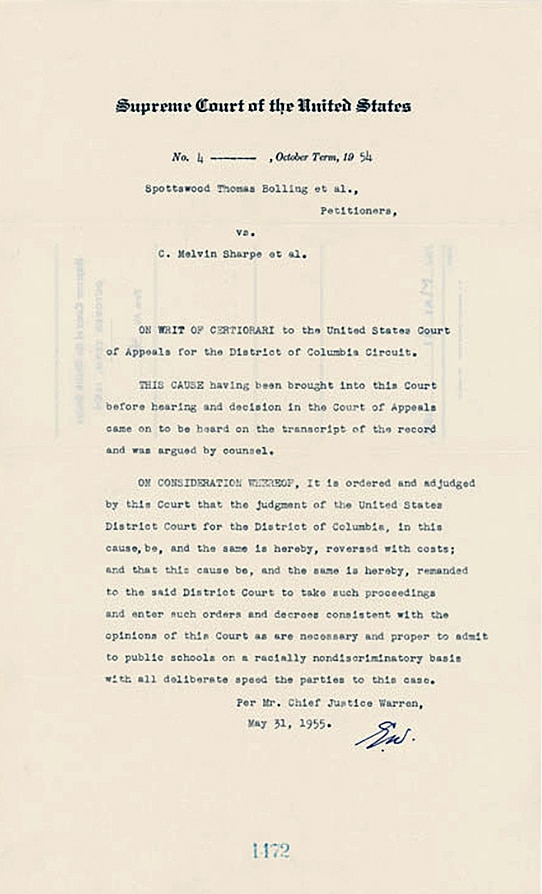

Bolling v. Sharp

1954

Bolling v. Sharpe (1954) was a companion case to Brown v. Board of Education, but it addressed a distinct legal issue: school segregation in Washington, D.C., which, as a federal district, was not governed by state law and therefore not directly subject to the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment—the constitutional basis used in the Brown cases.

Unlike the Brown plaintiffs, who sued state governments, the Bolling plaintiffs were challenging segregation imposed by the federal government.

The case arose when Spottswood Bolling Jr. and a group of African American students were denied admission to the new, whites-only John Philip Sousa Junior High School in the capital. Unlike the Brown plaintiffs, who sued state governments, the Bolling plaintiffs were challenging segregation imposed by the federal government. Since the 14th Amendment applies only to states, the Supreme Court instead evaluated the case under the Due Process Clause of the 5th Amendment, which governs federal actions.

In a unanimous decision issued on May 17, 1954—the same day as the Brown ruling—the Court, led by Chief Justice Earl Warren, ruled in Bolling that racial segregation in D.C. public schools was also unconstitutional. Though the legal route was different, the Court concluded that “discrimination may be so unjustifiable as to be violative of due process,” and that racial segregation imposed by the federal government was such a case. This created a doctrine of reverse incorporation, where the principles of equal protection were applied to the federal government via the 5th Amendment’s due process guarantees.

Bolling v. Sharpe ensured that the federal government could not maintain segregated schools, reinforcing the broader message of Brown and extending desegregation requirements to the nation’s capital. Together, the two rulings made clear that segregated schooling was unconstitutional everywhere in the United States, regardless of whether the schools were operated by states or the federal government.