RESOURCES

PEOPLE

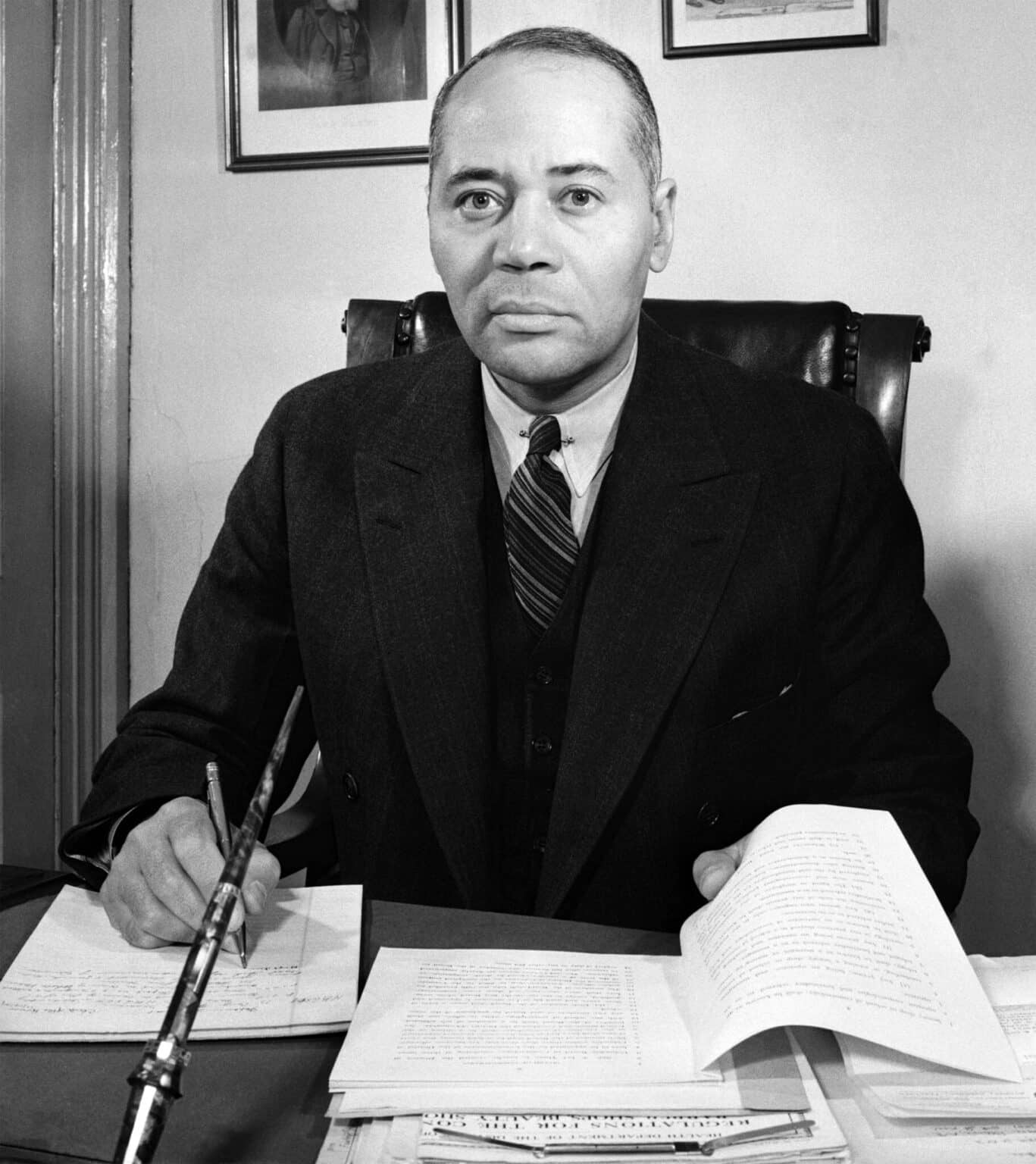

Charles Hamilton Houston

1895-1950

Born in 1895 in Washington, D.C., Charles Hamilton Houston was a lawyer, dean of Howard University Law School, and the architect of the NAACP’s legal strategy to challenge inequalities in education. The son of an attorney, Houston graduated from Dunbar High School in Washington and continued his education at Amherst College in Massachusetts, graduating Phi Beta Kappa in 1915. His experience as an infantry officer in World War I, where he witnessed the stark racial injustices faced by Black soldiers, steeled his determination to fight for equality through the law.

At Harvard Law School, Houston became the first Black editor of the Harvard Law Review, earning his LL.B. in 1922 and his J.S.D. in 1923. He pursued postgraduate study in Spain before returning to Washington to practice law with his father. While working in private practice, Houston began teaching part-time at Howard University Law School, then a night school for part-time students. In 1929, he was appointed vice dean, and over the next six years, he transformed Howard into a full-time, accredited law school and a national center for civil rights legal training.

Houston was a demanding and inspiring teacher, nicknamed “Ironpants” by his students. He urged them to become “social engineers” who would use the law as a tool for racial justice. As he put it, “Due to the Negro’s social and political condition, the Negro lawyer must be prepared to anticipate, guide, and interpret his group advancement.” Among the talented lawyers he trained were Thurgood Marshall, Robert Carter, and Oliver W. Hill—all of whom would later play pivotal roles in dismantling segregation. Houston deeply influenced Hill during his time at Howard, instilling in him a sense of mission and preparing him for legal battles in Virginia, where Hill would become a key figure in the NAACP’s litigation efforts.

In 1934, Houston resigned from Howard to become special legal counsel for the NAACP. He devised a long-term strategy to erode the legal foundation of segregation, beginning with the glaring inequalities in teacher salaries and graduate education. Houston recognized that directly challenging segregation’s constitutionality would likely fail in the courts of the 1930s, so he sought to make segregation economically and legally unsustainable. His approach focused on exposing how the “separate but equal” doctrine was a sham—and in doing so, laying the groundwork for future challenges to the system itself.

Houston’s campaign drew on deep community support. He understood that successful litigation required grassroots involvement—local NAACP branches would provide plaintiffs, resources, and energy. As he traveled across the South, particularly Virginia, Houston met with community leaders, documented unequal school conditions, and even produced a film showing the disparities in South Carolina’s segregated schools to galvanize local support. His efforts in Virginia were instrumental in organizing the NAACP State Conference of Branches and building partnerships with groups like the Virginia State Teachers Association. One of the first victories came in Alston v. School Board of Norfolk, which forced equal pay for Black teachers under the 14th Amendment.

Charles Hamilton Houston died of a heart condition in 1950 and did not live to see the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). The Brown case consolidated several local lawsuits, including Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, where Oliver Hill played a leading role. Hill and others carried out the legal strategy Houston had crafted—attacking segregation through rigorous litigation and constitutional principle.