RESOURCES

COURT CASES

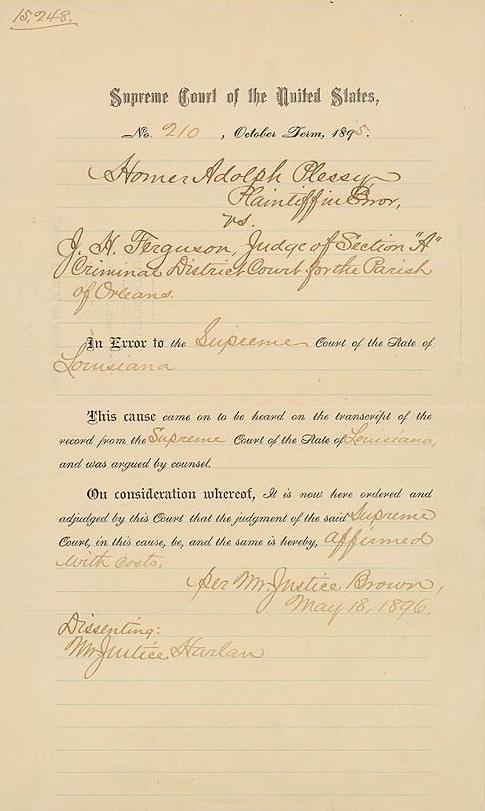

Plessy v. Ferguson

1896

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) was a pivotal U.S. Supreme Court case that legally entrenched racial segregation in American life for more than half a century. The case began in Louisiana when Homer Plessy, a man who was one-eighth Black and seven-eighths white, deliberately challenged the state’s 1890 Separate Car Act, which mandated separate railway cars for white and Black passengers. Plessy, with the support of the Citizens’ Committee to Test the Constitutionality of the Separate Car Law, purchased a first-class ticket and sat in the “whites only” section. When he refused to move to the “colored” car, he was arrested. His legal team argued that the segregation law violated the 13th Amendment (abolishing slavery) and the 14th Amendment (guaranteeing equal protection under the law).

The students of Prince Edward County and their allies turned Plessy’s logic against itself, proving that “separate but equal” was inherently unequal.

The U.S. Supreme Court, in a 7–1 decision, rejected that argument and ruled that “separate but equal” public accommodations for Black and white people did not violate the Constitution. Writing for the majority, Justice Henry Billings Brown stated that segregation did not in itself imply the inferiority of African Americans. Only Justice John Marshall Harlan dissented, famously warning that the Constitution is “color-blind” and that the ruling would become as pernicious as the infamous Dred Scott decision. The Plessy ruling effectively gave constitutional approval to Jim Crow laws, ushering in a legal era where segregation was permitted—and even encouraged—across transportation, housing, public services, and most notably, education.

This legal doctrine shaped the educational landscape of Prince Edward County, Virginia, and directly informed the conditions that led to the 1951 student strike at Robert Russa Moton High School. Like many Southern communities, Prince Edward County adhered to the idea that separate schools for Black and white children were legally acceptable—as long as they were nominally “equal.” But in practice, Black schools like Moton High were drastically underfunded, overcrowded, and lacked even the most basic facilities. Students were taught in tar-paper shacks and denied access to the same resources, extracurricular activities, and infrastructure available to white students.

When 16-year-old Barbara Johns and her classmates organized a walkout on April 23, 1951, their protest was not only against the physical conditions of their school—it was a direct challenge to the legitimacy of Plessy v. Ferguson itself. The students, aided by NAACP attorneys Oliver Hill and Spottswood Robinson, shifted the demand from “equal” schools to integrated schools. Their resulting lawsuit, Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, was later consolidated into Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Supreme Court case that ultimately overturned Plessy in the context of public education.

In this way, the legal precedent set by Plessy provided the very foundation that segregationists relied on to maintain unequal schools—but it also gave civil rights advocates a clear legal target. The students of Prince Edward County and their allies turned Plessy’s logic against itself, proving that “separate but equal” was inherently unequal.