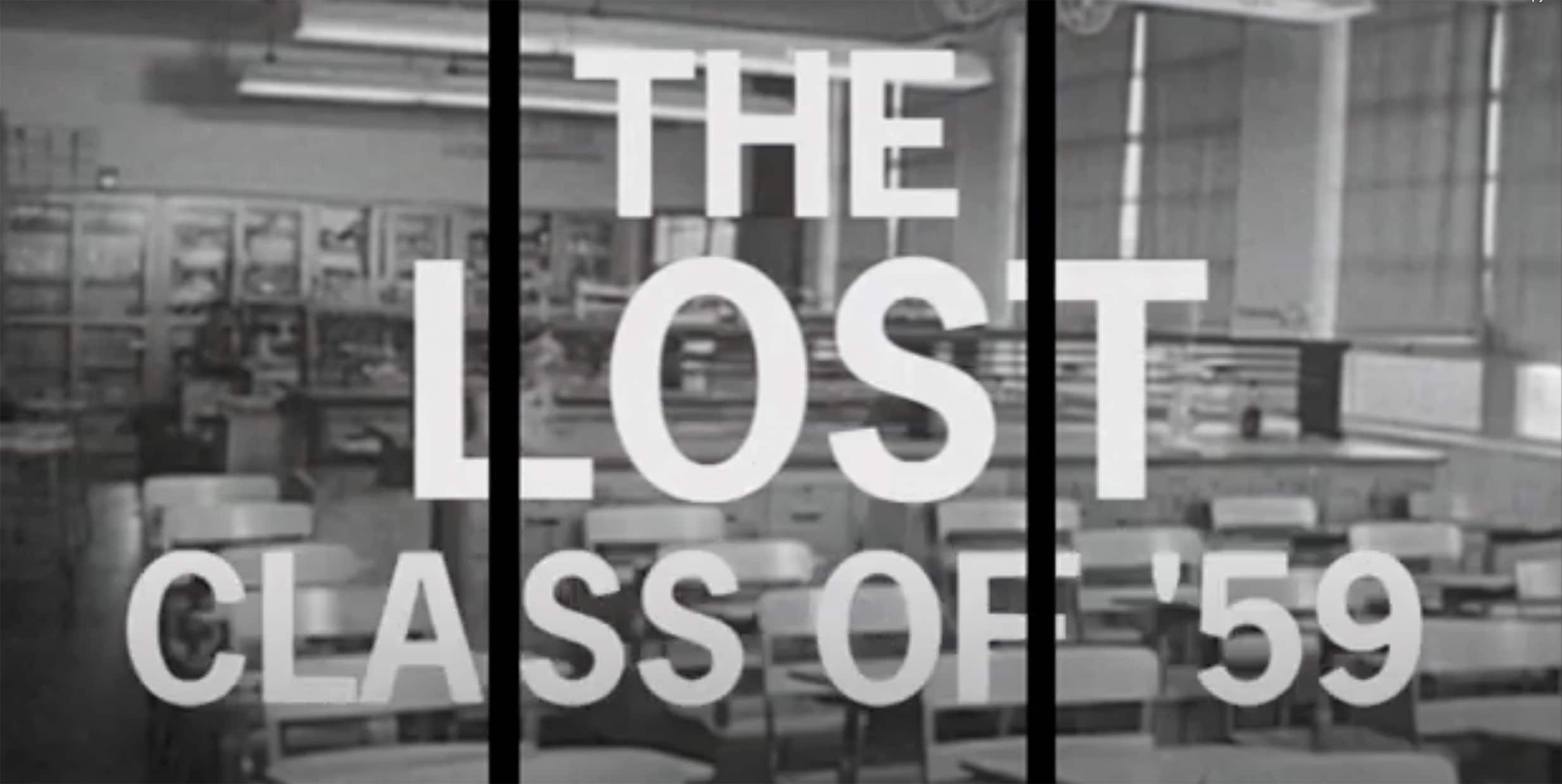

GALLERY V

PRINCE EDWARD COUNTY SAYS NO

“It is with the most profound regret that we have been compelled to take this action. We do not act in defiance of any law or any court. Above all we do not act with hostility toward the Negro people of Prince Edward County.”

— Prince Edward County Board of Supervisors, 1959

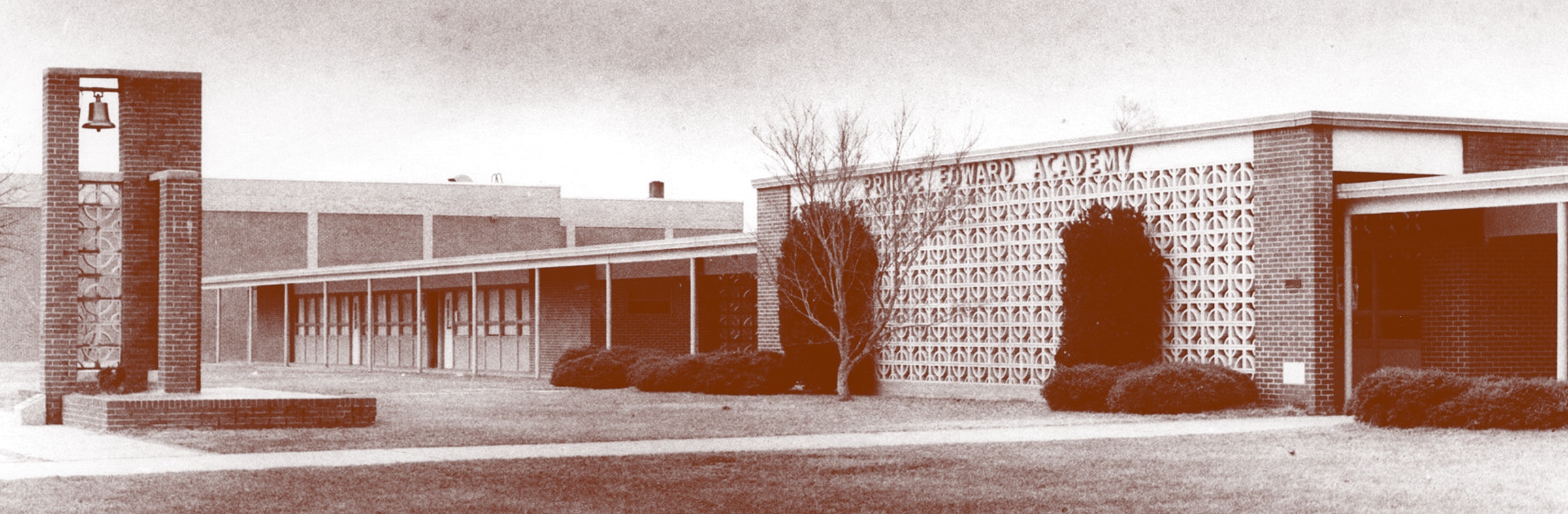

Segregationists organized a foundation to support private education, and in the fall of 1959 opened Prince Edward Academy. 1,446 children attended classes in 15 buildings, including churches. By 1961 the foundation constructed an upper (high) school. Another 1,700 children, shut out of public schools and excluded from the Academy, had few alternatives. Some children were sent outside of the county to attend school, but the majority remained at home, awaiting the outcome of the court challenge to reopen public schools.

PRINCE EDWARD COUNTY

SAYS NO

SUMMER

1959

WITH PROFOUND REGRET

TRAINING

CENTERS

REV. L. FRANCIS GRIFFIN'S LEADERSHIP

“The school closings are unethical, unChristian, and undemocratic.”

— REV. L. FRANCIS GRIFFIN

“I can visualize the world getting along without these 1,700 Negro children who are being frozen out of an education. But the tragedy to me is that it could happen in America, a nation whose swaddling cloth was the Bill of Rights, and not create any more excitement than it has.... We’re going to hold out for complete integration here.”

— REV. L. FRANCIS GRIFFIN, IN 1961 TO JET MAGAZINE

IN THE ABSENCE OF PUBLIC EDUCATION

— FLOSSIE WHITE

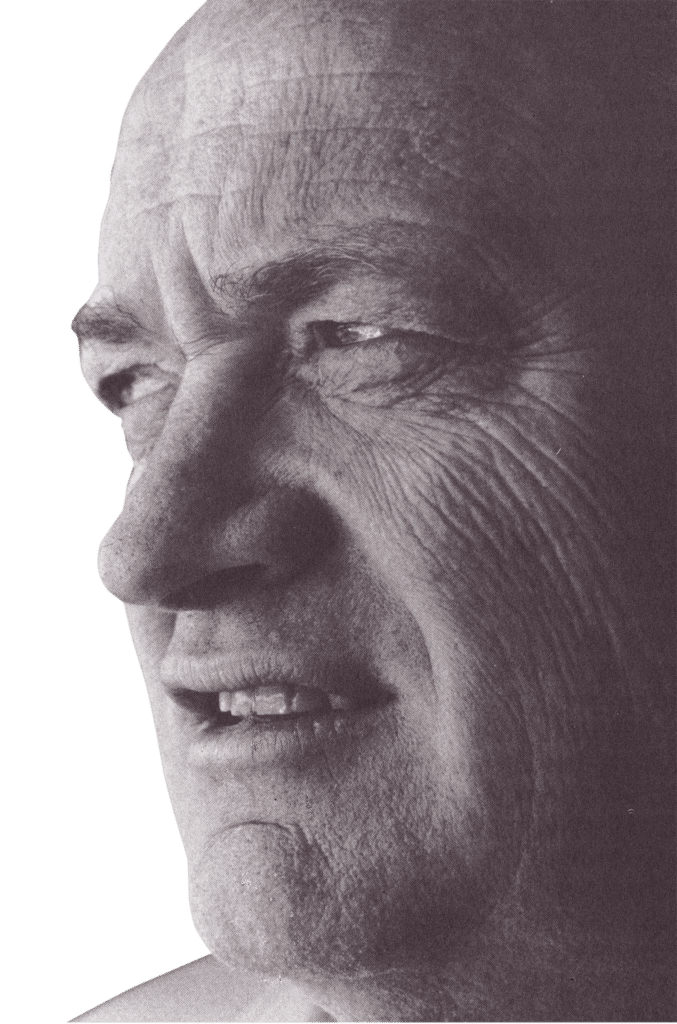

THE DILEMMA FOR GORDON MOSS

“He had a feeling for the underdog and hated bullies."

— PHILLIP LIGHTFOOT SCRUGGS, EDITOR, LYNCHBURG NEWS

“I have learned how much larger the racial issue really is, how it affects the life of the Negro, and I have come to see that not only should they have the right to integrated schools and the right to vote, but the removal of all things that brand them as second class citizens.”

— DR. C. G. GORDON MOSS

DR. C. G. GORDON MOSS

1899 - 1982

Earned BA from Washington & Lee

Earned MA and PhD from Yale

Chaired the Department of History and Social Sciences at Longwood College, as it was then called, from 1948–1960

Served as Longwood College Dean from 1960–1964

Taught until his retirement in 1969

Died in Farmville, Virginia

NAACP RALLY AT THE COURTHOUSE

MAY 21, 1961

“Roy Wilkins came to a crowded rally on the courthouse steps on a hot May afternoon in 1961 to urge Prince Edward Negroes who had fought to end public segregated schools not to settle for private segregated schools.”

— BOB SMITH, THEY CLOSED THEIR SCHOOLS

A PRIVATE NEGRO ACADEMY?

“That was more of a noble gesture, a community conscience-soother, than anything else.... There had been no attempts to find teachers.... And there had been no provisions made for buildings, no fund raising to support private negro education.... And no Negroes were invited to draw up the plans.”

— REV. L. FRANCIS GRIFFIN SPEAKING TO NEIL SULLIVAN IN 1963 ABOUT SOUTHSIDE SCHOOLS INC.

AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE

“We were a predominantly white organization that nobody had ever heard of before, that had no roots in the county, that proposed receiving children who were willing to go away to a distant place, maybe having to live with white families and go to predominantly white schools, and that required a lot of confidence building and a lot of courage of the parents to be willing to have their children taken away for months.”

— JEAN FAIRFAX, HEAD, AFSC’S SOUTHERN CIVIL RIGHTS INITIATIVE, INTERVIEWED IN 2006

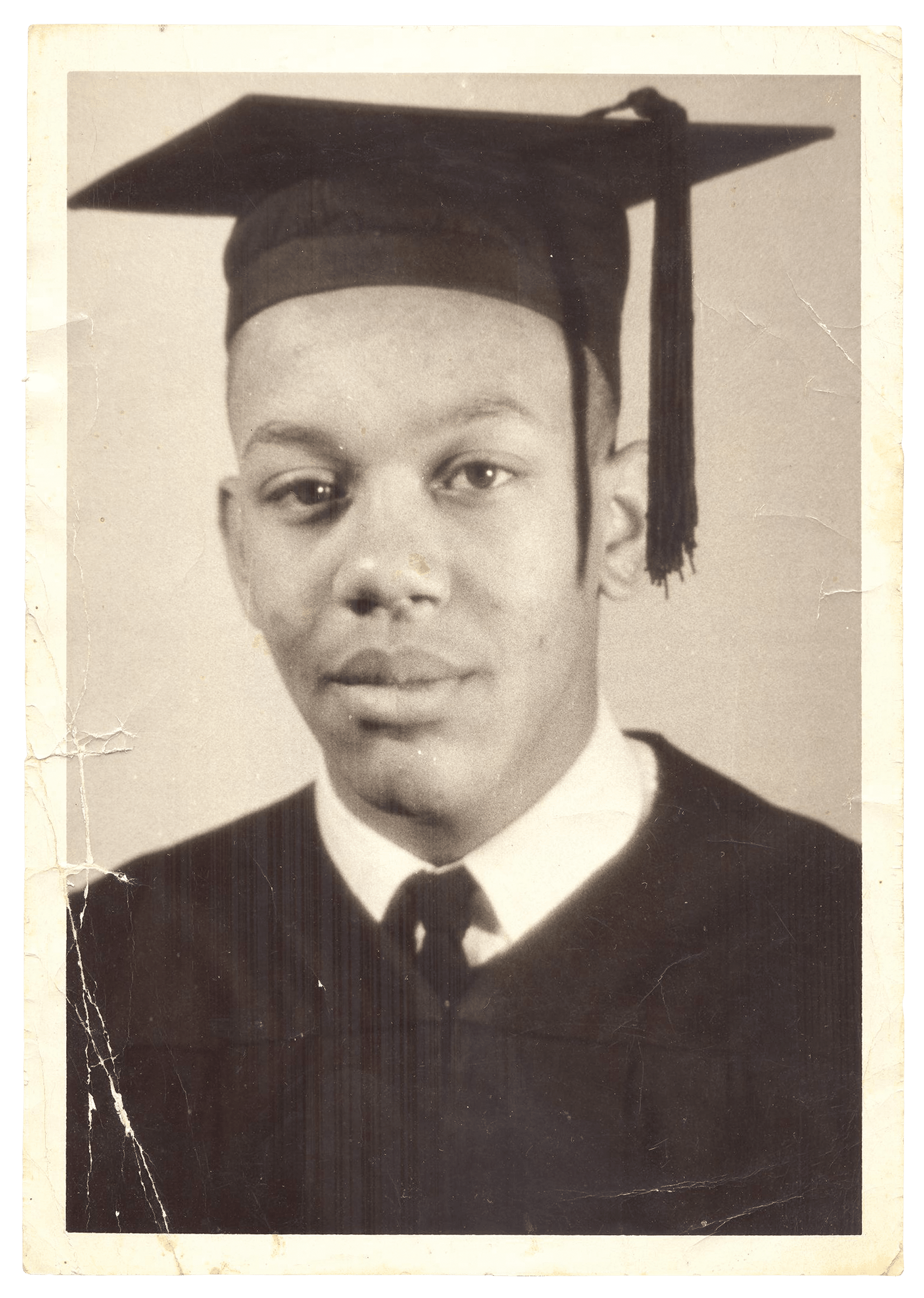

KITTRELL JR. COLLEGE

“The schools of Farmville were ordered to integrate, but their Educational Officials refused and instead, closed them. Fortunately, the Trustee Board of Kittrell College led by Bishop Frank Madison Reid, munificently offered each of the High School students a Scholarship which made a continued education possible for them…”

— EDITOR'S NOTE, KITTRELL BULLDOG, 1960

1959

SENIORS

Charles Taylor (Class Vice President)

Marie Walton (Secretary)

Mamie Evans (Corresponding Secretary)

Elsie Booker (Treasurer)

Flossie Oliver (Chaplain)

Fannie Turner (Parliamentarian)

McDonald Bagley

Ethel Barnes

Margaret Carter

Robert Crawley

Rosetta Hall

Robert Hamlin

Christine Irving

Pearl Redd

Henry Redd

Ernest Redd

Samuel Jackson

Arlean Ross

Barbara Scott

Helen Shepperson

Grace L. Sims

Bernice C. Smith

Ronald K. Ward

Ruby Watkins

James Wiley

James Wood

JUNIORS

Marilyn Brown

Patricia Davis

Phyllis Ghee

Annie Hicks

Dorothy Jackson

Willie Jones

Estelle Nash

Alfred Redd

Helena Redd

Viola Redd

Samuel Taylor

Mary Tompson

Phyllistine Ward

Lottie Wiley

SOPHOMORES

Doris Booker

Gretna Carpenter

Elsie Eanes

Lawrence Holloway

James Hudson

Pauline Jackson

Shirley Miller

Hattie Paige

Ralph Smith

Virginia Saunders

Lydia Walker

Dorothy Wood

1960

SENIORS

John Brown

Patricia Davis

Phyllis Ghee

Shirley Jackson

Willie Jones

Helena Redd

Viola Redd

Mary Thompson

Gwendolyn White

Lottie Wiley

1961

SENIORS

Hattie Paige

Sammie Womack

1962

SENIORS

Virginia Saunders

Farmville Students at Kittrell Junior College

“We have crossed the river, the ocean lies ahead.”

— CLASS MOTTO

“Fellow Kittrellites, Farmville Students, you who are now facing the problem, and those who will meet the challenge in future endeavorance, ‘the torch given by our Constitution and guaranteed by our United States Supreme Court, be yours to hold up high....’ ”

— EDITOR'S NOTE, KITTRELL BULLDOG, 1960

Robert Hamlin

STUDENT

VOICES

STUDENT VOICES

PRINCE EDWARD

ACADEMY

J. BARRYE WALL'S LEADERSHIP

“…He spent most of his waking hours on matters of Foundation business. He could be found in its offices directing the mailing of enclosures or helping to plot campaign strategy far into the evening.”

— BOB SMITH, THEY CLOSED THEIR SCHOOLS

PRINCE EDWARD ACADEMY OPENS

SEPTEMBER 1959

“In May 1959, the Prince Edward [school] Foundation had $11,000 in cash, $20,000 in three-year old pledges, no teachers under contract, no buildings, no school buses, and no other tools of education.”

“By September, the Foundation had to be ready to provide private education for approx-imately fifteen hundred white children in the county. ”— BOB SMITH, THEY CLOSED THEIR SCHOOLS

A PERMANENT CAMPUS

“Can any nation which claims that its members are free, deny parents the right to defend their children from associations which all the past experience of history and even the modern projections of sociology declare, early or late, will corrupt the racial integrity of his children ad infinitum, world without end.”

— PRINCE EDWARD SCHOOL FOUNDATION FUND-RAISING SOLICITATION, 1961

BUILDING THE FUTURE

THE UPPER SCHOOL OPENS

PLANNING THE

FREE SCHOOLS

“I hope that every American, regardless of where he lives, will stop and examine his conscience about this and other related incidents. This Nation was founded by men of many nations and backgrounds. It was founded on the principle that all men are created equal, and that the rights of every man are diminished when the rights of one man are threatened.”

— JOHN F. KENNEDY, RADIO AND TELEVISION ADDRESS, JUNE 11, 1963

REV. DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. VISITS FARMVILLE

MARCH 30, 1962

FARMVILLE, VA

“Things will get better… Do not despair, do not give up, but just stand firm for what you believe in, and people all over the United States will say there are black people in Prince Edward who have injected new meaning in the veins of civilization.”

— DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR.

JANUARY 1, 1960

RICHMOND, VA

“I do hope that citizens in that community will not accept the offer of private schools for Negroes. I hope they won’t sell their birthright of freedom for a mess of segregated pottage.”

— DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., SPEAKING IN RICHMOND, VA AT AN EMANCIPATION DAY RALLY

This section of Virginia is the bulwark of Harry Byrd’s political dynasty that holds Virginia’s liberal bent in a strangle-hold. The anti-NAACP laws, the infamous trespass ordinances aimed at thwarting the Sit-Ins, the Pupil Placement laws – all children of “massive resistance,” had their origin and loudest support from this same Negro majority section of Virginia that makes up most of the Fourth U.S. Congressional District.

LED BACKWARDS

It may well have been that the severe social change that is taking place in the South today might have been considerably accelerated had not Virginia, “the mother of Presidents” led the South backward into “massive resistance.”

It is refreshing, however, to observe even from this brief vantage point of the struggle’s history, that social crises at times produce their greatest need. The nonviolent thrust of the Negro community in the South and Virginia has met “massive resistance” with “massive insistence.”

This is a part of the aim of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference “People to People” program. I am convinced, as I have said many times, that the salvation of the Negro is not in Washington, D.C.

The Supreme Court, the Justice Department, the President of the United States, and the Congress can aid immeasurably in the emancipation process of the Negro, but the major responsibility of securing our full freedom depends upon the Negro himself.

Our constitutional guarantees will not be realized until Negroes rise up by the hundreds and the thousands, community by community, and demand their rights through nonviolence and creative protest.

As our SCLC task force traveled over the Black Belt of Virginia last week, I could see the potential of this. In just two days, we touched the lives of nearly 10,000 people. We could see the deep hope and yearning for freedom in the eyes of thousands of Negroes and the sincere commitment to human equality in many whites.

100,000 POTENTIAL

The Black Belt of Virginia has a potential of 100,000 voters in the Negro community but there are barely 17,000 registered at the present. The Fourth District is similar to many parts of Mississippi with many Negroes who are tied to the land as sharecroppers. Economic suppression is the rule rather than the exception and the poll tax requirement adds to the burden of general apathy in Negro voter registration. It is towards

(Continued on Page 12)

THE KENNEDY ADMINISTRATION TAKES ACTION

“We may observe with much sadness and irony that, outside of Africa, south of the Sahara, where education is still a difficult challenge, the only places on earth known not to provide free public education are Communist China, North Viet Nam, Sarawak, Singapore, British Honduras—and Prince Edward County, Virginia.”

— ATTORNEY GENERAL ROBERT F. KENNEDY, MARCH 18, 1963 AT THE KENTUCKY CENTENNIAL OF THE EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION

PREPARING FOR THE FREE SCHOOLS

WHO WILL LEAD THEM?

“Suddenly, then, my mind was made up. I would tell the Free School Trustees they had hired themselves a superintendent.”

— NEIL SULLIVAN, BOUND FOR FREEDOM

IN ONE MONTH

“I had to get four buildings cleaned and repaired and get twenty buses running. I had to get textbooks and supplies ordered and staff a cafeteria. And somehow, in a county that had seen its experienced teachers move away one by one during the past four years, and in the face of a national shortage of 100,000 teachers, I had to find one hundred qualified teachers.”

— NEIL SULLIVAN, BOUND FOR FREEDOM

REACHING A COMPROMISE

“The choice was an inspired one. For almost two months in that summer of 1963, Bill vanden Heuvel, with consummate tact, had twisted arms of influential people, both white and negro, in the county and in the state of Virginia, forcing them into a position where, finally, they had found it possible to compromise and agree to a plan for reopening schools.”

— NEIL SULLIVAN, BOUND FOR FREEDOM

“The project [the free schools] owes its success to the heroic efforts of many individuals… The trustees of the Free School Association are among them. They were six unusual men—three white, three negro, all Virginians and all in the highest ranks of their state’s academic circles.”

— SEN. ROBERT F. KENNEDY, 1965

THE SUMMER OF 1963

“We aren't drop outs.

We are lock outs…”

“Four years on the street is four years too long...”

“By the end of summer it was noted that almost no casual conversation between Negroes and whites in downtown Farmville occurred.”

— ROBERT L. GREEN, “THE EDUCATIONAL STATUS OF CHILDREN IN A DISTRICT WITHOUT PUBLIC SCHOOLS,” COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY, 1964